When we say a song is “in tune,” we usually mean in tune with A440 — the modern global reference for pitch.

But centuries ago, there was no universal standard. A note called “A” could mean 415 Hz, 430 Hz, or even 460 Hz, depending on where — and when — you played.

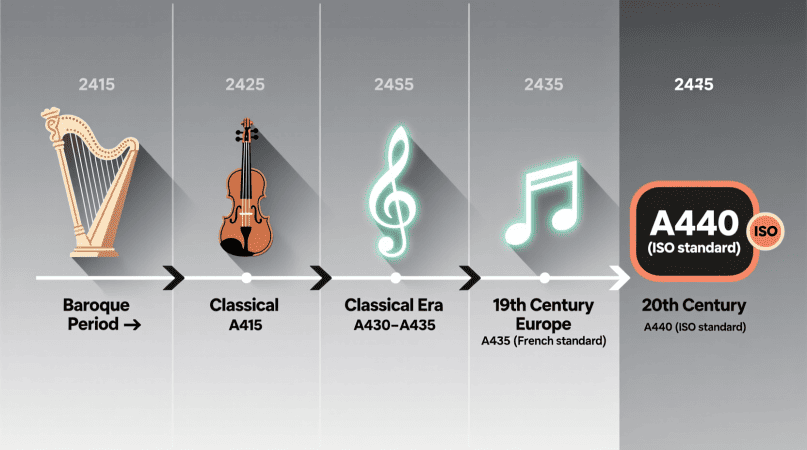

This article traces the fascinating evolution of historical pitch standards, showing how regional, technical, and cultural differences led to the stable tuning systems we use today.

The Problem: “A” Wasn’t Always A440

Before the 20th century, musicians tuned by ear or by comparison to a reference instrument (like an organ, tuning fork, or pipe).

Each orchestra, church, or court developed its own “local pitch.”

That meant:

- Two “A”s in different cities could differ by up to a semitone (≈50 Hz).

- Traveling musicians constantly had to retune or even swap instruments.

- Ensemble blending between regions was nearly impossible.

The Baroque Period — A415 Hz

During the 17th and early 18th centuries, most European ensembles used A415 Hz, roughly a semitone lower than modern A440.

| Era | Approx. Pitch | Region | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baroque (1600–1750) | A415 | Central Europe | Warm, mellow tone; less string tension |

| Early Classical (1750–1800) | A421–430 | France, Italy | Gradual rise in pitch for brilliance |

| Romantic (1800–1850) | A430–450 | Germany, Austria | Increasing brightness and orchestral power |

The Baroque pitch (A415) is still used today in period performance ensembles to replicate the authentic sound of composers like Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi.

👉 If you want to test this tuning, adjust your reference pitch in your Pitch Detector to 415 Hz — your A will sound slightly lower and smoother.

The 19th Century — Pitch Inflation

As orchestras grew larger and concert halls bigger, conductors began raising pitch for more brilliance and power.

This led to a phenomenon called pitch inflation — each ensemble wanting to sound “brighter” than the next.

By the mid-1800s:

- France: A ranged between 435–445 Hz

- Germany & Austria: Often A450+ Hz

- England: Some opera houses reached A455–460 Hz (almost a semitone higher than Baroque!)

This caused chaos for singers — a higher pitch meant greater vocal strain, especially in opera.

Something had to be standardized.

🇫🇷 The French “Diapason Normal” — A435 Hz

In 1859, France passed a law defining A = 435 Hz as the official reference for tuning.

It was called the Diapason Normal, meaning “normal pitch.”

Many European countries adopted it soon after — it became the first government-approved pitch standard in history.

But due to temperature and measurement inconsistencies, A435 didn’t spread globally.

By the early 1900s, some countries had already drifted toward A440 Hz.

🇬🇧 The London Agreement (1939) — A440 Hz Wins

In 1939, the British Standards Institute and international delegates agreed to make A440 Hz the new standard “concert pitch.”

Why 440?

- It sat between earlier regional standards (435 and 450 Hz).

- It worked better with the emerging equal temperament system.

- It was convenient for manufacturing and calibration.

In 1975, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) reaffirmed it as ISO 16:1975, which still defines A440 today.

Read more: A440 Tuning Standard Explained

Why Different Eras Chose Different Pitches

Several factors influenced historical pitch variation:

| Factor | Impact |

|---|---|

| Instrument Design | Older strings, pipes, and reeds couldn’t handle high tension. |

| Climate & Temperature | Heat raises pitch — colder climates favored lower tuning. |

| Regional Preference | French orchestras liked brightness; German ones liked warmth. |

| Vocal Range | Singers in Baroque and Classical periods preferred lower A (415–430 Hz). |

| Technology | Electronic tuners didn’t exist — pitch drift was inevitable. |

Your Pitch Detector solves this instantly by locking to an exact reference frequency — something musicians 200 years ago could only dream of.

Historical Pitch Standards — Timeline Overview

| Period | Standard | Approx. Year | Region / Adoption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baroque | A415 | 1700s | Central Europe |

| Classical | A430 | 1800s | Austria / Italy |

| Diapason Normal | A435 | 1859 | France |

| Philharmonic Pitch | A452 | 1890s | Britain (Royal Philharmonic) |

| London Standard | A439–440 | 1939 | International Conference |

| ISO Standard | A440 | 1975 | Worldwide |

Modern Variations — A440 Isn’t the Only Option

Even today, some orchestras use alternative tunings:

- A442–A444 → Common in European symphonies for brightness

- A438 → Preferred by some string ensembles for warmth

- A432 → “Verdi tuning,” claimed to sound more natural (scientifically, only 0.32 semitones lower)

Most digital pitch detectors, including ours, let you select any base frequency manually.

Try it in the Accuracy Tests or Voice Pitch Analyzer.

How Pitch Detectors Adapt to Different Standards

When you change your reference pitch:

- The detector recalculates its note-frequency map.

- Each detected frequency is compared against the new base (e.g., A432 instead of A440).

- Output adjusts accordingly — all relative intervals stay the same.

So, whether you’re using Baroque A415 or bright A444, the math remains consistent — only the starting reference point changes.

Learn the formula in our Accuracy Calibration Guide.

FAQ — Historical Pitch Standards

Q1: Why did Baroque music use A415?

Because instruments of the time favored lower tension, producing a richer and warmer tone ideal for strings and voice.

Q2: When did A440 become universal?

It was officially standardized in 1939 (London Conference) and confirmed by ISO in 1975.

Q3: Why do some musicians use A432?

It’s a modern reinterpretation believed to create a “softer” tone — but there’s no acoustic advantage beyond preference.

Related Reading

To see how modern tools analyze tuning, the overview of machine learning in pitch detection shows how algorithms adapt to different standards.

Browser-based tools apply these ideas in practice, as explained in real-time browser pitch detection.

When comparing old and new recordings, understanding privacy-first pitch detection helps keep analysis secure.

Fine historical differences are easier to spot using the guide on sticky ±cents.

If you notice multiple readings on early instruments, the explainer on why tuners show multiple notes clarifies what’s happening.

Readers new to tuning theory often check whether pitch and frequency are the same before comparing standards.

To connect theory with software, the article on can a pitch detector detect musical notes shows how modern tools interpret tuning.

PitchDetector.com is a project by Ornella, blending audio engineering and web technology to deliver precise, real-time pitch detection through your browser. Designed for musicians, producers, and learners who want fast, accurate tuning without installing any software.